We have seen that any depiction of a collection of objects combines them into a single composition of forms which can be connected temporally as well as spatially. It was one of Einstein’s mathematics tutors, Herman Minkowski, who in 1908 proposed that we should regard this combination as spacetime. Although Minkowski was the first to mathematically formalise those properties of spacetime which fitted the latest physical theory of his day, spacetime was widely employed in the pre-scientific era. Take for example, medieval maps of the world, such as the Mappa Mundi in Hereford Cathedral.

Figure 4, Hereford Mappa Mundi: Eden, the Temptation and Expulsion

What makes this map as difficult for lay people to read as a Minkowski diagram is that it plots historically separated events as well as geographically separated places! For example, the successive stories of the Garden of Eden, Noah’s Ark and Exodus are all shown at places on the map that successively approach the city of Jerusalem at its centre. At the top of the map, Eden appears as a now inaccessible island on which we see the first humans, Adam and Eve. Then we see them redrawn outside of Eden as an angel expels them from that Earthly paradise for disobeying their creator. Jerusalem is at the centre of the map because for medieval Christians, the resurrection of Jesus in that city marks an origin for their faith in the afterlife which he promised. Jerusalem is also a physical destination, because a pilgrimage there is the most important journey of a pious lifetime.

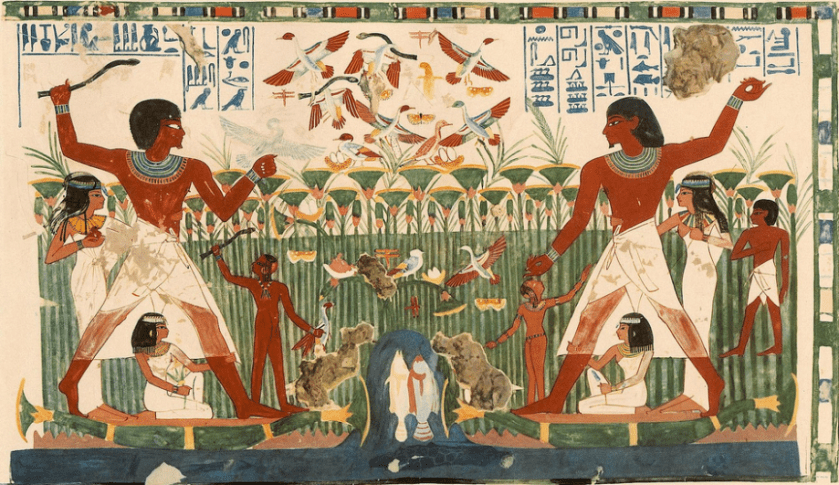

For ancient Egyptians, the River Nile had a similar significance, as is evident in the tomb painting commemorating the life of the courtier Menna shown in Figure 5. Contrary to the impression that this picture shows a meeting between two boats carrying different groups of people along the Nile, it is a serial composition that shows Menna and his family using the same boat to fish and hunt wildfowl in different excursions along the one life-giving waterway running through a desert kingdom.

Figure 5 Mural from the tomb of Nakht, Luxor, 15th Century BCE

These two artistic examples show that there is more than one way of composing a picture, and numerous ways of narrating events that depend upon stylistic conventions. We may be tempted to say that the Egyptians were better at narrating episodes than medieval monks, because they could draw things more naturalistically. However, the signature style of Egyptian figure drawing which shows torso to the front and head and legs in profile is not as naturalistic as the style found in Renaissance European art. The discovery of perspective geometry and the visual foreshortening of objects in that period offered further narrative opportunities, as seen in the mural depicting the life of St Peter in Figure 6.

Figure 6, Masaccio, Episodes from the life of St Peter, c. 1427, Brancacci Chapel, Florence

Although not so obvious, Figure 6 is also a serial composition, because St Peter in the yellow robe is shown both on the left healing a cripple and on the right, later raising St Tabitha from the dead. Masaccio’s use of a single light source coming from the left also adds a solidity to his forms that is lacking in the ones depicted in Mappa Mundi and Nakht’s mural. Thus, stylistic techniques also play an important role in conveying information and mood in a picture. Since the history of art reveals an enormous variety of pictorial styles, there appears to be no single catch-all definition of what a picture is, or what it can communicate. Within the history of ideas, of which art is a part, we see a multiplicity of alternatives, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

The stylistic rebellions of 20th Century European art, literature and music have made scholars cautious of viewing their history as one of progress from “primitive” styles such as that of Mappa Mundi to more sophisticated, developed ones such as those of the late Renaissance. Historians of science have been less cautious, because science is viewed as a truth-giving activity which can demonstrate by means of experiment and allied technology that today’s ways of thinking are better than earlier ones.

In common with historians of art, I believe that we should exercise caution in classifying older ways of thinking as more backward than current ones. Caution is particularly required in cases where science resurrects ancient philosophical debates. For example, the block universe account of event ordering resurrects a metaphysical argument known as “eternalism”. That argument runs back through St Augustine to Parmenides in the classical period. It was controversial then and remains so now. Likewise, the notion that spacetime is a physical entity (a “field”) resurrects an unresolved controversy in the Enlightenment about whether space and time are concrete properties of perceivable objects or abstract notions of the relationships between them.

I use the history of picture-making as the narrative thread for this book about time and temporality because it offers two great advantages: A) Pictures provide by far the longest record of human expression and communication – reaching back some 40,000 years. B) Their compositional methods are highly instructive about what we believe can or can’t be true.