I’m trying to complete a book on the visual representation of time which I started writing many years ago. I’m using this site to test out some ideas, in the hope that this may help me finish the book before Time finishes me. Constructive comments and suggestions are always welcome.

Time is invisible, yet pictures describe it well. Drawing the shortest line between two points A and B on this page shows how the interval s separating them may be viewed as either a distance or a time:

A______________________________________________________________________________________________B

- Distance: s is the shortest path between a pair of places A and B.

- Time: s separates an event where a pencil marks A from an event where it marks B.

While 1) presents s as an interval separating a pair of places that appear together, 2) presents A & B as the positions of events that appear successively. A pencil tip need not travel between places in order to be present in successive events, but it must do so in order to draw a line between A & B. Thus, a drawn line doesn’t simply mark a series of places; it records the sequence of actions that construct it.

If we think of time as the “period” over which that sequence of drawing actions occurs, then we can use the speed at which the pencil tip travels from A to B to define the length of the period separating them. Yet whatever that speed is, it doesn’t alter the positions of the marking actions that connect A to B. This explains why many scholars think it better to view time as a series of events rather than a period defined by a rate of motion.

But this notion of time as an event series poses the question of what “events” I am in when I see the pencil at A and then at B. I know that these pencil events “occur” in my mind and believe they could do so in other minds, even if their viewpoints are different. I might then reason that my brain “tells me” that A and B are public events which occur on a desk that is in a different place to my brain.

However, this brain sometimes dreams that I’m drawing at my desk. So, it’s always left to me to judge whether the pencil, paper and desk in these events are public objects or dreamt ones. Furthermore, the way in which I validate my beliefs about these public and private worlds makes this ‘I’ appear as much a social construct as a chemical one.

We validate our beliefs about a public world by agreeing to classify closely matching private experiences as facts. Physical theories present events (including brain activity) as public facts. But it’s difficult to prove that physical events exist independently of individual experience and reasoning, because individual minds are the only place in which events certainly occur.

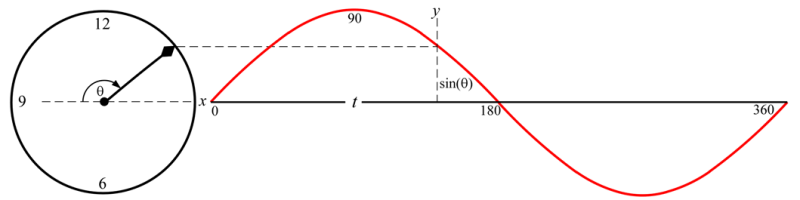

Physical theory sidesteps that problem by making the pragmatic proposal that regardless of where an event occurs, it can be defined as an object at a place at a time. The object is defined by an amount of mass at a point, its place is given by measuring rods which show the distances separating it from others, and its time is given by the display of any clock that remains next to the object. This notion of a physical event identifies an expanse of event positions that is called spacetime, in which, clock time t is one of four geometric coordinates, x, y, z, t, needed to define any point event position.

The clarity of this approach has helped scientists to overtake philosophers and priests as the arbiters of current thinking about the relationship between observers and the objects of their experience – particularly because scientists can support the spacetime account with experimental proofs. Nevertheless, the concept of time is so fundamental to human thought that it doesn’t belong to a single discipline. It is studied in all, regardless of whether they are classified as sciences or humanities.

But the most obvious challenges to everyday ideas about the nature of time are made by the spacetime model of Relativity Theory. It demonstrates that two observers who are relatively separating at a velocity v approaching light speed c will agree that the other’s clock appears to be running at a slower rate that diminishes to 0 at v = c. Yet this relative difference between clock rates doesn’t prevent either observer from detecting the same physical events, even if each sees them in a different sequential order.

For many physicists and philosophers, this shows that any collection of physical events is ordered like an extended block of points which simply “is” and no more changes than does the line AB! According to this “block universe” view, all point-like physical events are in their places, regardless of what rate any clock appears to run. Hence, period length, tA–tB, does not appear to be an essential property of the physical world, even if it is a useful notion for brain-operated observers. And block theorists would argue that labels like past and future merely indicate which event positions are +t or –t relative to the t coordinate of any one event at which one observer “is present”.

In common with other challenging theoretical notions such as “parallel universes”, this block universe one equates the form of the physical world to that of a mathematical model. Yet we don’t need to be scientists to recognise that models and diagrams have properties that clearly differentiate them from the objects which they seek to represent! One of the aims of this book is to assess which properties of a picture most likely match those of the world that it claims to represent.